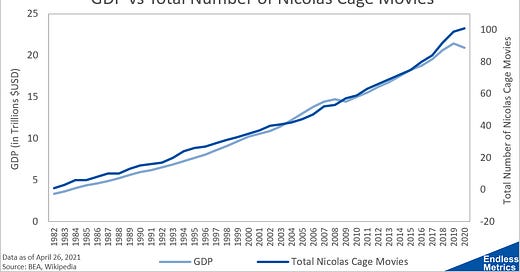

Let’s say you’re a busy manager and one of your analysts comes to you and says they’ve found a variable that has 99% correlation to GDP that could present powerful way to forecast the economy. Sounds promising, so you take a look at the historical data:

You are skeptical of whether or not Nicolas Cage is really responsible for the entire U.S. economy but, since you are so busy, you say go ahead and build out the model.

The analyst comes back and has great news. The regression model has a 98.7% adjusted R Square, a statistically significant intercept, a statistically significant coefficient, and also passes with a statistically significant F-test.

But, that’s not all. The analyst took it one step further and took the average number of Nicolas Cage movies over the last five years and assumed that he would continue making that many movies, on average, over the next ten years.

That doesn’t seem outlandish to you and the model results seem amazing, so you ask the analyst to benchmark the model’s forecast for the economy against the official forecast of potential GDP from the Congressional Budget Office. The analyst comes back with the benchmark:

You are shocked but the forecast speaks for itself! You get ready to present this amazing finding to the CEO and start to wonder if you should publish these results more broadly to get a social media campaign going to promote more Nicolas Cage movies to stimulate economic growth for the country.

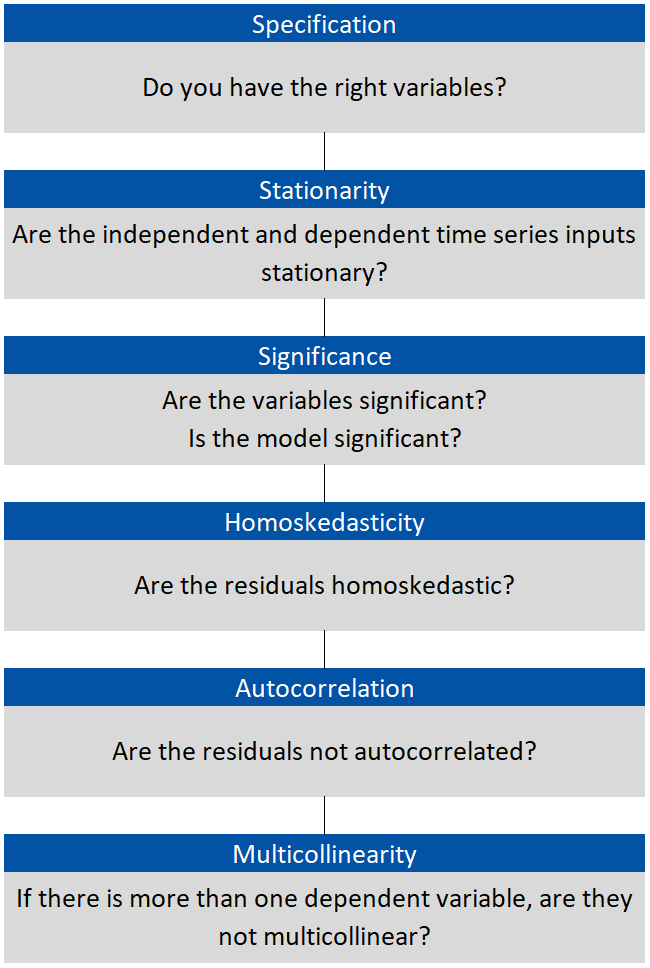

But, just before you do that, you remember an article about models being dangerous and some regression modeling guardrails from this guy who writes a daily newsletter that annoyingly overfills your inbox. You ask your analyst to run the guardrail tests in the recommended flowchart:

Defeated, your analyst comes back and says that the model didn’t satisfy every test. The analyst really believed in the specification that there was a relationship between the Nicolas Cage and the economy and had a significant model and variables. Furthermore, it was a simple one-variable model, so multicollinearity wasn’t a factor. Unfortunately, stationarity, homoskedasticity, and autocorrelation failed.

You don’t have time to understand what all of that stuff means but you are concerned about breaking the guardrails in an unfamiliar intellectual domain. So, you tell the analyst that this was a great effort and to keep looking for a model that can satisfy all the tests.

You shelve the analysis and decide against showing it to the CEO (or anyone else) and are happy that you questioned a model to see if it was good or bad. For a brief moment, you wonder if there really is a connection between the economy and Nicolas Cage movies. But, then you realize you have a lot of work to do and your inbox is overflowing with stupid newsletters to delete. So, you go back to your busy day as a manager, browsing random articles on the internet after closing this one.

Links

Yesterday’s Post | Most Popular Posts | All Historical Posts | Main Site | Contact